Having a reserve is important – it is the last chance one has, especially when flying with higher rated wings when a collapse may result in a wing that cannot be recovered. They are also often required in a mid-air collision, or should one have suffered structural failure, such as line breakages. More rare is when one experiences medical problems in the air.

Material – normally is of a porous nylon type that is very

susceptible

to UV damage. Sharp or rough objects also easily damage it. Rust can

damage.

Velcro can damage.

Lines – are usually stretchable, can be damaged by objects, Velcro

and UV exposure.

When fluids other than water are spilled over reserves, or the harness

gets dunked in the sea, the reserve should be removed from the pouch,

thoroughly

rinsed in clean water and left to dry in the shade. Best is inside a

room

with the curtains closed. UV is a big enemy of the material. One can

blow

it dry with a fan but no heat. When it is dry and it is sure that it is

clean, it can be repacked.

Reserves are usually tested by parachute standards. They are

dropped from a specified height (80 – 100 m) with a weight attached and

it is measured how fast they deploy and descend.

Both DHV and Afnor rate reserves, but there are many unrated reserves in the world. The testing of reserves have sparked many debates in the past. Many manufacturers climb on the bandwagon of easy money as everybody requires a reserve. This also happened in South Africa, where at one stage everybody with a sewing machine would try and copy a reserve. Well-known manufacturers in South Africa were PISA, Chute Shop and Paralogic. Paralogic no longer exists, and the other two do not generally make hang glider or paraglider reserves any longer. These three worked in accordance with the PASA standards. There are reserve copies floating around that probably do not conform to any standards. Many of the South African copies were based on the PISA reserve.

Some of the well-known rated brands are Apco, Charly, Pro-Design,

Metamorfozi,

to name but a few. There are more with rated models (not mentioned

here)

but there are also many unrated brands. The question always has been:

how

do we know that a model is good if it is not rated or tested?

Reserves are tested to descend at 6.8m/s at the maximum weight.

Some come down slightly slower, but they should not be faster. The

lighter

you are on a reserve, the slower you will come down. But it is not

ideal

to have a too big reserve as it may become unstable.

The CEN standards are trying to make it compulsory for reserves to come down slower than the 6.8m/s standard. They are looking at 5.5m/s. That means that reserves will be bigger or that they will have to be made from a less porous material. A bigger reserve could cause hassles when they have to be packed into the very small pouches that some harnesses have.

Manufacturers are already looking at making them slower. There are already reserves rated at less than 4m/s at 120kg.

As descent rates are often based on size of the reserve, the reserve is bigger. Bigger reserves open slower, generally and are sometimes more expensive. So the question has to be asked: how important is a slower descent rate?

The rule of thumb is: Any reserve is better than no reserve. Even if

it would be too small for the all-up weight of the pilot, it is better

to have it than not to have it.

It is very important that a reserve is deployed in stages. First

the bridle must be stretched, then the lines must be stretched, and

only

then must the canopy deploy. Should the lines not be stretched when the

reserve starts opening, a malfunction can occur.

Hence it is important that the packer knows what he is doing, and

what

can go wrong. The packer must ensure that the reserve will not be

caught

in the pouch, or that the lines can wrap over it, or that the reserve

is

deployed prematurely.

There are many different deployment bags. The most favoured is the

pocket type or bag type. The 4 leaf clover bag type is also very

popular.

As long as the nappy allows deployment in the correct sequence, it does

not matter what deployment bag is used. Some packers will favour

specific

bags to other types.

The disadvantage of some bags are that the lines cannot be stowed inside the nappy. It then lies loose in the pouch and can get tangled, or dirt and dust and even twigs can get inside the pouch at times, and damage the lines. All these things can also lead to malfunctioning on deployment due to lines tangling.

In harnesses with a pocket for the reserve, or that have an airbag externally attached, it is important that the nappy has a side attachment point for the deployment handle. If it is attached to the center of the deployment bag, then the bundle gets tilted and catches against the sidewalls or the airbag, making it extremely difficult to extract.

All the nappies that allow the lines to be stowed inside or in a special side pocket usually work very well and protect the reserve and lines properly. These include the Apco type nappy – a 4 leaf type with a long bungee attached - that works really well.

There are other gimmicks that are used to make the bag go up rather

than down. They have extra “ears” that slow them down (the idea is that

the pilot will fall faster than the reserve in that case).

Most malfunctions happen due to packing problems.

Problems arise when a pilot “locks” his pouch because the reserve has fallen out, or the handle has a tendency to pull out. When he needs it, he cannot deploy it.

In some older harnesses that have Velcro closures the Velcro can get “welded” together, and it takes great strength to pull the two sides apart. The time required would be too long.

Normally one loses the nappy and handle when one has to deploy one’s reserve. Some pilots decide to save the money they would have to spend should they throw the reserve by attaching the nappy to the canopy or lines or somewhere. A number of times this has lead to malfunctioning. The nappy can tangle in the lines and cause the reserve to not deploy properly. One pilot put a loop around the reserve lines, thinking that the nappy would stay at the bridle end. The reserve deployed beautifully but then the loop shifted up along the lines, closing the reserve mouth. The inevitable happened.

Almost any manner of attaching the nappy to the reserve or bridle may lead to a malfunction. It is not worth the worry to save those few Rands, unless you think that the money is worth more than your life.

Other types of packing problems that can occur is not pulling the apex down on a pull-down apex reserve. The reserve cannot deploy in that case. Forgetting folding aids in the reserve such as lines or clips will definitely lead to malfunctions.

It has also happened that the Velcro on the sides of the harness had “welded” together. The reserve deployed, but the side holders for the bridle on the harness did not open. The pilot went down head first.

Another problem that has to be checked for is that a reserve that is put in a pouch that has to be pulled from the side or where an airbag is also fitted, has been put in the correct deployment bag. The handle MUST be attached to the side of the deployment bag and not the center. If the handle is fitted to the center the bundle will tilt and jam against the sides of the pouch, and make it impossible to get out or at the very best, very difficult.

It has also been experienced that the handle was not attached properly to the deployment bag and came apart from the nappy on deployment, either by tearing out or just disintegrating. Big warning on this: a handle cannot be stitched on to the nappy directly! In that case it WILL tear out.

We have received reserves packed into acceptable deployment bags,

but

because the packer did not understand how the deployment bag functions,

he packed it incorrectly, making it almost definite that there would be

a malfunction.

LOOK at the handle – even experienced pilots have grabbed the

wrong thing when they did not look first. One can lose precious time.

GRAB the handle – and pull it out while one starts to

LOOK around for open air

THROW the reserve as hard as possible in the direction least

likely to get it tangled in the glider. Sometimes it is better to throw

it downwards.

Then pull in the glider. Easiest is to grab one center A-line, or the stabilizer line on the tip. (Should the reserve be attached to the shoulders of the harness, and the glider is not pulled in, the pilot will come down faster due to the reserve and the glider “fighting” each other. The pilot may land very hard on his back, causing severe damage.)

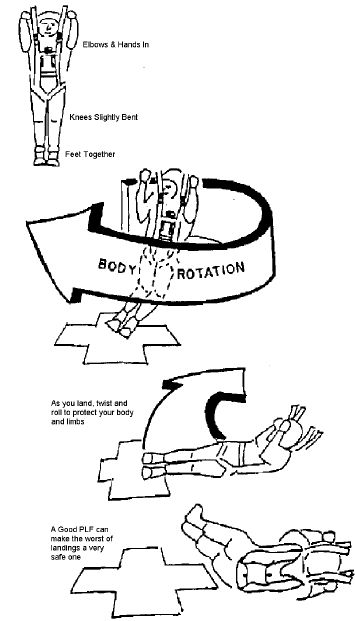

Be ready to do a PLF

.

.

SAHPA does not have packing licences for reserves as yet, but it

is intended to finalise this item some time during 2003. Have your

reserve

packed by someone who has a good reputation in the sport, at present.

There

are quite a few good packers, but there are some who claims to have the

knowledge but are making mistakes. We are trying to reach these packers

to inform them, but pilots often do not remember who packed their

reserves

when they were packed the last time.

It is planned to introduce a packing card to be kept with the reserve or harness to make it easier to track the packer.

Laura Nelson

July 2003

Impact and protectors, in German, http://www.notschirm.ch/crash.htm

A general writeup with some pictures and tables in German http://www.lahmeente.de/rettungsgeraeteartikel.htm

For those interested in how the reserves get DHV tested.

In English http://www.perche.com/Englisch/produkte/rettung/Oeffnung.htm

In English http://www.parachutehistory.com/eng/denalt.html

And some more info in German

http://www.schmidtler.de/html/ht_technik/rett.htm shows some examples

of reserves who failed the DHV tests.

Why reserves have a limited life span ...

http://www.schmidtler.de/html/ht_technik/rettalt.htm is a report

testing 10-20 year old reserves,

2 out of 5 disintegrated on the first test. The remaining 3 had a slow opening

time and would not have passed the test.

To pass DHV, a reserve has to handle 3 openings with

maximum specified weight with an

opening speed of 150km/h.

Corresponds to a 80m free fall. Or about 4 seconds. Pilots tend to take at

least 4 seconds to decide to deploy.

After the 3 deployments the reserve is not allowed to show any damage

Another test checks that a reserve has to be fully inflated within 60 meters once deployed. This gets tested by

throwing the

packed reserve without container together with a 70kg weight.

The faster falling weight has to be able to pull out the reserve within 60 meters.

To determine the sinkrate the reserve gets dragged behind the static load vehicle which also gets used for

PG and HG

load tests at a constant speed.

From the drag force one can calculate the cw and from there the sink speed

for a certain

weight.

Those sink speeds from manufacturers are probably based on sea level air

density. In South Africa we can be flying from sites which are

1600m higher.

Anyone feels like calculating how much extra factor we got on sink speed

compared to a sea

level sink rate?

The DHV specs in German

http://www.dhv.de/typo/fileadmin/user_upload/aktuell_zu_halten/technik/tec_downloads/lbaltf.pdf

And in poor English

http://www.dhv.de/typo/fileadmin/user_upload/aktuell_zu_halten/technik/tec_downloads/aw_specs.pdf

In December 2004, during the All Africa, two foreign pilots were dragged badly after needing to deploy their reserve parachutes during strong winds.

The one was dragged through 2 fences. This has bothered and worried many pilots.

In all the years of flying, I have never heard of a method to collapse the round reserve after being deployed, especially during strong wind

situations. I assumed it was because one could not easily reach the reserve, which is very true in the case of the 5m-6m bridles of a hang glider pilot.

It was always presumed that one would either be dragged, or have a hook knife to cut free, or have some sort of quick release for the reserve. These solutions are not easy, no matter how positive one is in mind.

Fairly recently, there have been reports that some people have attached an additional handle and line to the parachute centre apex line to pull to collapse the reserve. I have not yet seen one of them, so in my opinion that could be tricky, as such a handle has to be SAFELY stowed and be easily available when needed, and in such a way that it could NEVER interfere with the reserve while deploying or perhaps inadvertently keep it from deploying.

As harnesses differ, it might make it necessary to modify each harness.

In the windy weather we have now, flying is not always possible, and in our case we decided to try out a possible solution that we recently heard about for this problem on Sunday, 21 August 2005. The Edenvale Sportsfield is excellent for such experiments.

We used my Apco Contour harness and Apco Mayday pp18 (i.e. quite a big reserve, as reserves go). The first deployment from standing dropped the packet safely behind the pilot! We then shook it out in the wind (which was

gusting from approx 12kph to 25+kph). The pilot was nicely jerked off his feet and started being dragged, but managed to pull the reserve in very quickly via the bridle, then went onto the centre apex line, pulling in until the reserve was completely flat. This could be done very fast.

We tried this a few times, also when the wind was stronger. There was always some dragging but not as much as we have experienced with just using a paraglider while routinely practicing abort techniques. This led us to the

conclusion that if one can get rid of the glider, it is possible to stop the dragging by a reserve parachute before one gets seriously injured.

Then it was time to attach a paraglider as well, without the option of quick release carabiners, because most of us do not have that choice.

Even though we used a very old, quite porous, small paraglider and the wind seemed to be less gusty, there was enough power on the combined units to

drag even a heavy pilot quite severely. It became clear that it was imperative to get the glider in first, then go for the reserve. This caused the pilot to be dragged over the paraglider, helping to keep the paraglider

from re-inflating. The reserve could then be pulled in and collapsed quite quickly, even by a light pilot.

This exercise has put our minds at ease about being dragged after deploying a round reserve. One definitely does not need to go through fences.

Recommendations

1. After a reserve deployment, follow the text book instructions. Pull in the glider if at all possible.

2. Do everything as required, i.e. a normal parachute landing fall, etc, when reaching the ground.

3. Should the pilot then be dragged, and the paraglider is inflated for whatever reason, pull in the paraglider first by abort techniques that would work quickly and easily (e.g. pull in on one riser

until the glider is no longer inflated, etc). Expect to still be dragged by the reserve at this point, but the speed will be far less than with both units, and it is quite likely that one will be dragged over the glider (at

least that happened everytime during the practice sessions).

4. Pull down on the bridle and grab the centre apex line

of the reserve by putting a hand through the outer lines of the reserve. (In future I will mark all parachute centre apex lines with red or black koki pen, about 20cm above the connecting point at the bottom, to make it easy to recognise.) Keep pulling in on it until the reserve parachute is totally deflated.

5. Once it has been collapsed, keep hold of the centre line to prevent the parachute from re-inflating, and stand DOWN WIND from the glider and reserve, in order to ensure that any re-inflation will create

no danger to the pilot (a re-inflating glider or reserve will just blow around the pilot and cannot drag him). Then get out of the harness, and bundle everything together.

IMPORTANT: Do not panic when the dragging starts, but immediately start getting the glider in, and then the reserve.

Doing nothing, having no plan of action in such cases, is when one gets injured very easily. Knowing what one can do and trying to do it (i.e. being mentally prepared), even if it had not been practiced before, is half the

battle won.

This windy Sunday turned out to be very productive, in the end, and good fun.

Best regards

Laura Nelson

NS&TO, Paragliding

22 August 2005

Safety Notice – Reserve parachute deployment problems - 23 Aug

Incorrectly mounted reserve parachutes, handle attachments, and velcro closures

are mostly the reasons for malfunctions or difficulties with reserve parachute

deployments. This was highlighted again by the Xntrix Club reserve deployment

evening and recent repacks. Such problems could create situations where an

attempted deployment could lead to a fatal accident.

Case 1

The first problem was with a rear-mounted tandem reserve. The reserve was a Gin

Tandem, in its factory fitted deployment bag. The harness was a big Fun2Fly

Explorer harness. The reserve deployment handle was incorrectly attached to the

centre attachment point and the handle line was also incorrectly routed, which

made the handle line too short. In other words, the handle pulled tight against

the nappy before it could pull on the pins. Even standing with a foot against

the harness and pulling with both hands did not dislodge the pin. The problem

here was resolved by moving the handle attachment to the side attachment point

on the nappy and routing the handle line correctly.

It is imperative after a reserve repack to test that the pins will fairly EASILY

come out when the handle is pulled. The check should be done by the packer, BUT

the owner of the whole system should satisfy himself that the pins will be

released on pulling the handle. It is YOUR life that is dependent on this. One

can do it by pulling slowly on the handle while watching the pin(s), to the

point just before the pin(s) would slip out of the closure loop(s). The packer

should not mind demonstrating that it works. Even if it does slip out, the

repacker should be able to refit the pin within a minute or two.

Case 2

One of the Xntrix evening ‘casualties’ was a Papillon steerable reserve that had

been moved from a front mount pouch to a bottom mount underseat pouch of a UP

Teton II harness. As the reserve was not actually made for a bottom mount

harness, the risers are a bit short. These were then extended with additional

bridles of more than one meter length (one on each side). This would have made

it impossible for the pilot to reach the toggles on the risers to steer the

reserve. In addition the incorrect handle attachment point (the centre

attachment point) on the nappy was used, causing the handle to pull against the

nappy and not the pins when pulled. The pilot found it impossible to release the

pins in the practice deployment. Also problematic was the amount of velcro on

the harness. Even with all the pulling, the velcro holding the handle line could

not be released by the pilot. Later, in checking how easily the velcro on the

tubes protecting the bridles would open, it was found that only with great

effort the velcro parted, and not at all close to the top of the harness. It

could have resulted in the pilot hanging lopsided after a reserve deployment.

Three issues in this case then.

Firstly the risers – do not just extend a steerable reserve’s risers without

checking. It could render the reserve useless as a steerable. To resolve the

problem in this case, the original risers were attached to the shoulders as

intended, and the bridles routed down the one side of the harness. Part of the

reserve’s lines had to be put in the side tube as the risers are too short to

reach the bottom pouch, but they were then covered with a loose piece of

material to protect them from the velcro of the tube, also dirt that could

penetrate the area, as well as from UV where they are exposed for a short

distance between the tube and the pouch. This material is not attached anywhere

or sewn together, as it should be able to fall off freely when the reserve is

deployed.

Secondly – wrong attachment point on the nappy was used. When the deployment

handle was moved to the side attachment point of the nappy, this made all the

difference. After changing the risers and the nappy attachment points, and

reducing the velcro on the tube for handle line, the pilot could deploy easily

on a second practice session.

Thirdly – velcro is so handy, but a real curse when there is a lot of it.

Especially when it has not been opened regularly, even over a short time it

welds together extremely securely. This harness is by no means the only one that

has this problem – there are many of them. Some years ago one of our pilots went

down head first after a reserve deployment over water (luckily) due to the

velcro failing to open on the side tubes for the bridle on a Fun2Fly harness. To

ensure easier opening on harnesses where a lot of velcro had been used to close

the deployment handle line and bridle tubes as well as the shoulder piece on

top, fit small pieces of opposite part velcro at critical points on the closure

(preventing normal closing between the sewn on strips). This will ensure that it

will run free easier.

Open all velcro parts regularly (once a week or max two weeks) to facilitate the

opening when required in the event of a reserve deployment (make it part of the

pre-flight checks).

Near a reserve the effects of velcro can be terrible, especially in the vicinity

of the lines. Lines are often severely damaged by velcro. Make sure that the

lines cannot easily get in contact with velcro, anywhere.

Case 3

A pilot had trouble to get his Apco Mayday pp16 reserve out of the rear mounted

pouch of the Apco Contour harness that had a Cygnus airbag fitted. The reason is

that due to the airbag, the reserve could not fall free when the pin is pulled.

Hence one has to remove the stitching on the side of the pouch so that the side

flap will fold out flat and the reserve can be pulled out sideways. Easily done

and problem solved. (Also happens often with Fun2Fly Explorer and Easy Seat and

any similar harnesses that had airbags fitted, and/or where a centre point nappy

attachment for the handle was used.)

Case 4

A pilot had a problem pulling the Apco Mayday pp18 reserve parachute free of the

side mounted pouch on a Woody Valley X-act harness. This happened because the

tube for the bridle is extended into the pouch and the end of it was attached to

the outer edge of the top flap, towards the centre. When fitted, this

effectively put the bridle over the reserve. The pilot was pulling more forwards

and up to release the reserve, and the bridle and tube locked the reserve into

position in the pouch. Only when the pilot pulled more outwards did it release.

The bridle tube end was re-routed so that it is no longer attached to the top

flap, and the problem should not re-occur, no matter which way the pilot pulls

the reserve.

Case 5

Speedbar lines tangled with reserve on attempted deployment. The pilot could not

throw the reserve.

Make sure that the reserve handle and bridle is routed OVER any speedbar lines.

Case 6

Lost handle on rear-mounted reserve without handle line tube, during deployment.

I honestly do not know how one would resolve this problem except by modifying

the harness by fitting a piece or two of webbing (with a small piece of velcro)

between the handle and the pouch that can prevent it from falling to the back.

There is NO solution if the handle line is NOT routed through a tube held by

velcro on the side of the pouch, e.g. Fun2Fly harnesses and many other

harnesses. If there is such a tube or webbing, which many harnesses have, then

one can reach down and get the handle again, even though with some difficulty,

as it will not have fallen too far, but at least there is something one can do.

Case 7

Rubber bands disintegrating and going gooey is very common, especially where

reserves have not been repacked recently. Where the goo went through the reserve

parachute material, it has to be cut out and repaired as the goo can go gooey

again in hot weather, and make the material stick together and cause a

malfunction on deployment. Where the goo is very old, it might go extremely

hard, damaging the fibres and weakening them. (Had a recent case of rubber band

goo damaging a sailplane reserve through 4 layers of material.)

Nappy attachment points

To ensure that a nappy (deployment bag) can be correctly used for the harness or

pouch it is fitted to, it is VERY important that nappies have at least two

attachment points for the handle – one in the centre and one on the side. Most

modern nappies have these. The older nappies should be (correctly) modified in

order to be safe.

The emphasis on the correctly modified attachment points are important – an

attachment point can pull out of the nappy if not correctly done. That involves

having webbing stitched on the INSIDE as well as the OUTSIDE of the nappy for

making the attachment point on the webbing. Make sure that YOUR nappy’s handle

attachment points are correct.

Although it is possible to fit any nappy to any pouch, it reduces failures by

having adaptable nappies. Rear mounted and bottom mounted reserves work better

with side mounted handle attachments while front mount pouches are normally more

effective with a centre attachment for the handle. It depends on the shape of

the side mount reserve pouch on which handle position will work best.

Laura Nelson

NS&TO, Paragliding

22 August 2005